What American Progressives Get Wrong About Socialism

Universal healthcare, free education, and green energy programs are all great, but they are not socialism.

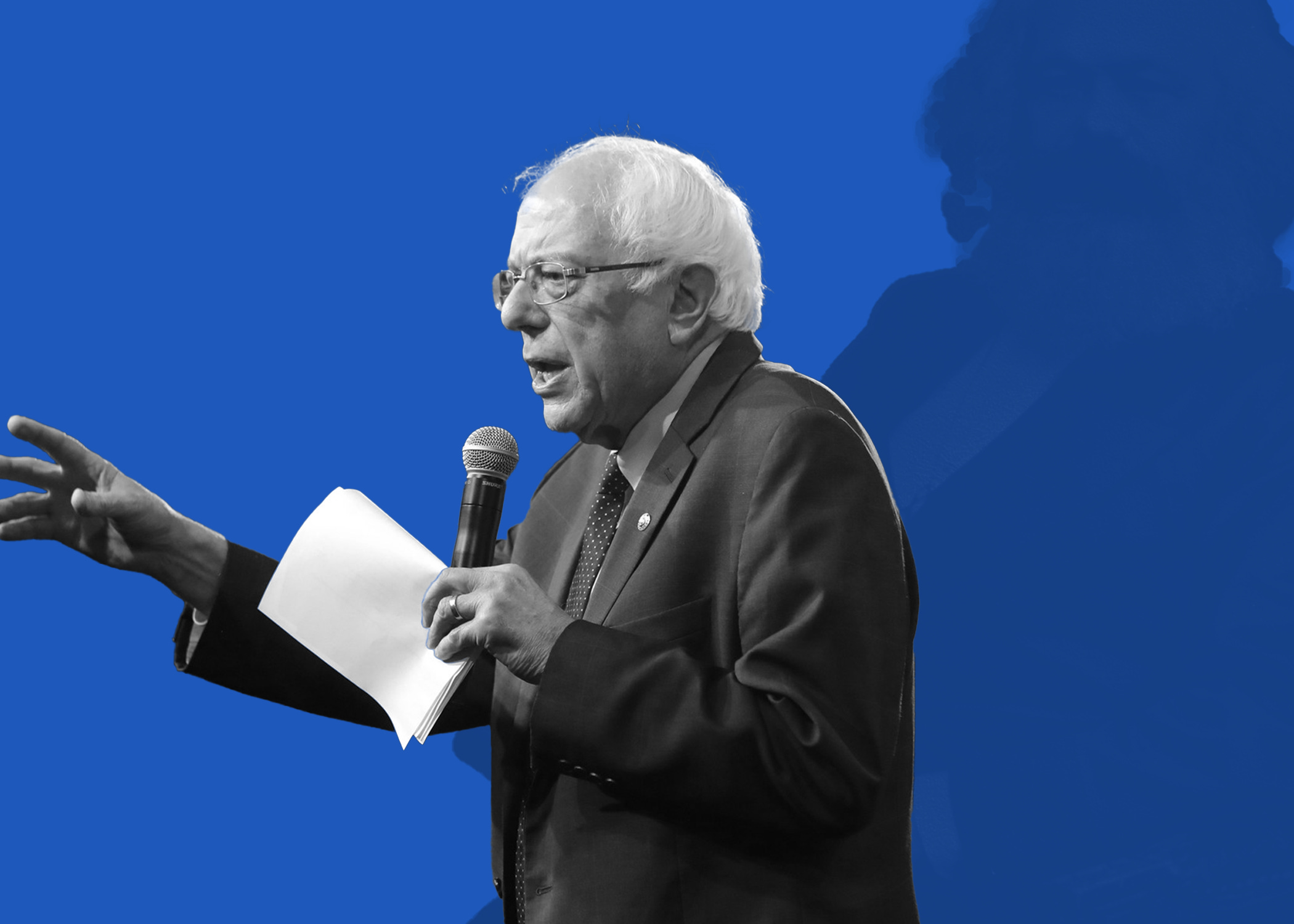

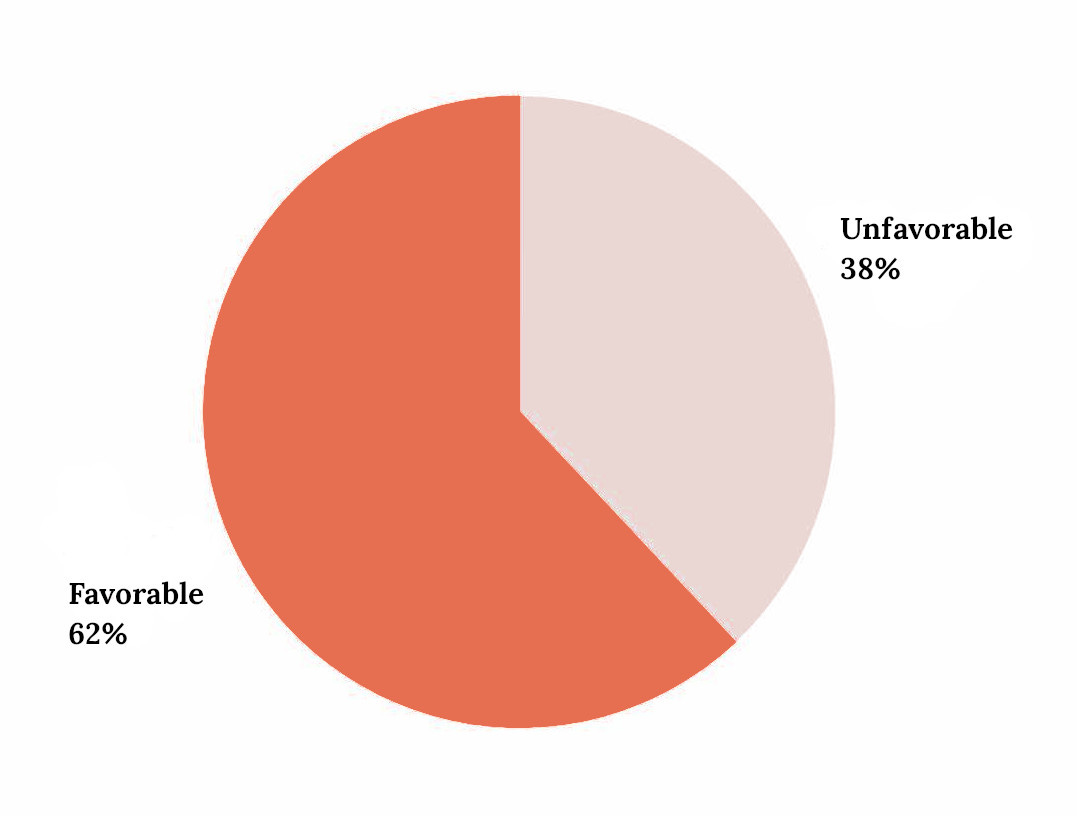

When Senator Bernie Standers stepped into the presidential arena in 2016, he reintroduced the word socialism back into the fore of the American political zeitgeist for the first time in nearly a century. Not since the days of Eugene Debs had a prominent U.S. figure made the term a part of the national conversation. Sanders’ greatest political contribution wasn’t a single policy, but the shot of life injected into long-dormant political machinations once thought buried by decades of Red Scare and Cold War propaganda. For the first time in recent memory, a majority of Americans under 30 hold a favorable view of socialism, thanks at least in part to figures like Sanders, “The Squad”, and other progressives who’ve ascended to elected office across the country and now occupy an increasingly robust and prevalent independent media sphere.

That being said, whether it be one of these modern socialist figures or their acolytes across media and the electorate, their definition and understanding of socialism tends to be neutered, marked by imprecision, or vague. Approach any AOC voter and ask them what socialism means to them, and they may tell you it’s about expanded social programs, human dignity broadly, or, in her own words: “what we see in the UK, Norway, in Finland, in Sweden.” These countries enjoy (in some ways) a higher standard of living, social programs not instituted in the United States like universal healthcare access, and somewhat more stringent regulation of capitalist enterprise, but, as many on all sides of the aisle have been astute to point out, are not technically socialist. Noam Chomsky, the prominent left-libertarian intellectual of “Manufacturing Consent” fame, likened Bernie Sanders to “mainstream New Deal Democrat[s]”, while the Heritage Foundation has an entire article dedicated to debunking the “myth” of Scandinavian Socialism.

Well-meaning social democratic strains within industrialized nations have fought ardently to secure collectivist social welfare programs out from under the business class in times of economic vulnerability, perhaps with the good faith intent of reforming society more holistically over time. However, the overall posture of these societies remains squarely capitalist. In many cases, even in Europe, these social reforms are beginning to fall victim to reactionary forces seeking to claw back influence and wealth, and Social Democratic parties are beginning to wane in influence as reactionary parties across Europe, like the AfD in Germany, have become increasingly popular, following in the Republican example of weaponizing economic anxieties, latent prejudices, and working class language to mobilize vulnerable masses against scapegoats, such as immigrants and the queer community.

But the erosion of social well-being has little to do with fringe minority groups eating from a pie that is plenty large enough to sustain an even greater human corpus than that which already exists, nor some kind of “cultural poisoning” ascribed to groups that a large enough plurality of people do not possess any willingness or means to try and understand and empathize with. Instead, the internal, unconscious logic of capitalism itself necessarily ordains that wealth, resources, and influence be increasingly concentrated into a shrinking capitalist class that should seek to preserve itself. To truly be a socialist is not to be committed to incremental social reforms, but to recognize, understand, and proselytize this aforementioned critique, while seeking to systematically unravel this state of things in favor of a more democratic economic arrangement.

In the long term, the only way to win is to unapologetically embrace and sell this narrative.

America’s 20th Century Tango with Social Democracy

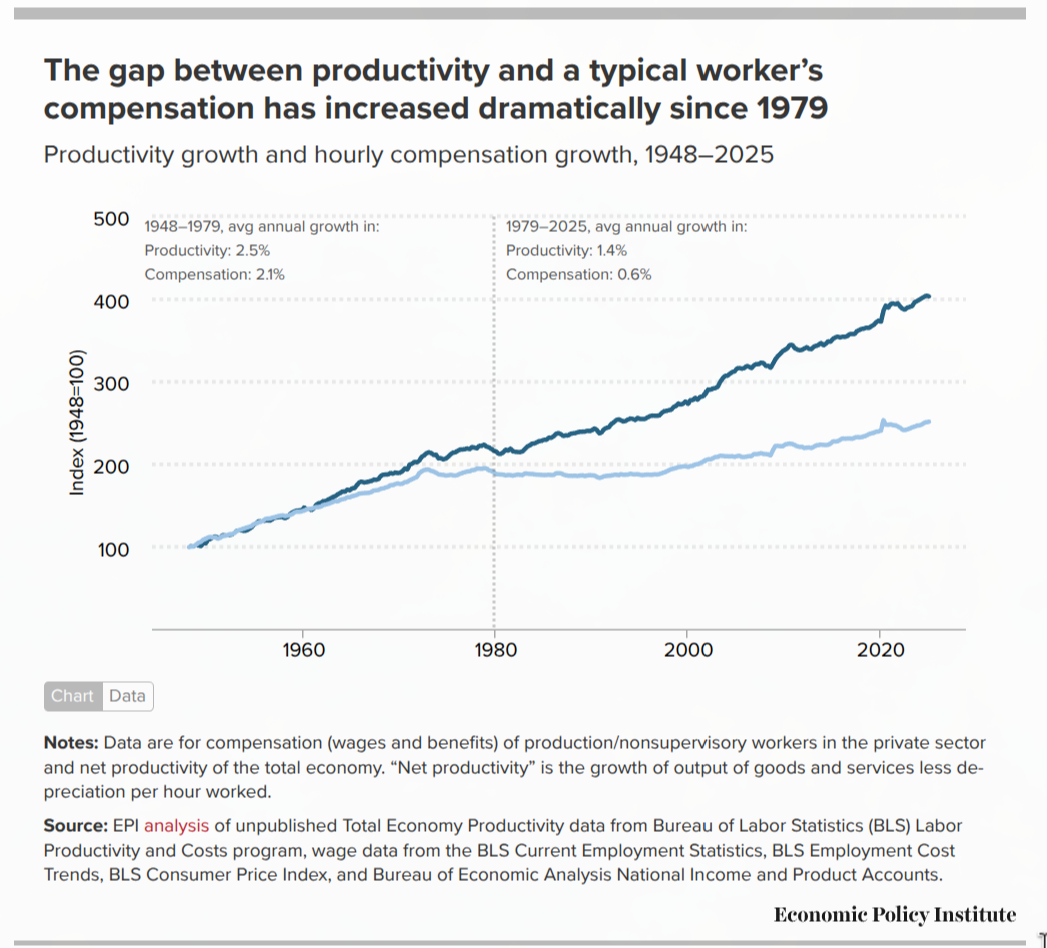

Earlier, I alluded to the declining focus on social welfare in Europe. But even the United States once enjoyed a progressive era marked by policies that could be likened to the priorities of more contemporary Social Democrats in Europe and even America’s own progressives. Europe’s declining focus on social welfare is in many ways evocative of America’s own transformation from the New Deal era into our prevailing neoliberal1 era. The last 70 years have visited upon the American public the slow degradation of the reforms offered up in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society as those that characterize post-World-War-II Europe. Granted, these programs were not self-referentially “social democratic” projects; in the 20th century, “social democracy” referred to a political movement which sought to usher in a classically socialist economy via gradual reforms, not unlike many of the self-described Democratic Socialists of our contemporary age, but the term has evolved in modern times to signify a willingness to simply regulate capitalism in lieu of replacing it outright. Nevertheless, in light of the bipartisan capture of Washington by corporate interest groups via Citizens United, Taft-Hartley, and other corporatist legislative and judicial victories, these social welfare programs, which have increasingly become relatively meager when compared with America’s staggering wealth and productivity gains, have been gradually disemboweled over time as much of the rest of the world outclasses the US in social welfare.

The American government was once ostensibly and, in many ways, substantively oriented towards the expansion of the labor movement, social safety programs, and healthcare access, at least domestically. It wasn’t a perfect record; the same sort of neocolonial international exploitation that has since exploded in application was being practiced even in the 20th century, and minorities were often barred access from the fruits of America’s social services (if not always overtly, often through institutional engineering, as seen in practices like redlining, officially endorsed by the Federal Housing Administration). Still, over the course of 40 years starting nearly a century ago, a reigning and unshakably popular Democratic Party delivered Social Security in the name of ameliorating America’s increasingly sizable elderly poor, Medicare and Medicaid in the interest of expanding healthcare access, the National Labor Relations Board to facilitate disputes between employers and unions impartially, the Civil Rights Act which outlawed segregation, and programs like the Public Works Administration which employed millions in the midst of the Great Depression and modernized America’s infrastructure (much of it still in use today, like the Hoover Dam). Hell, Harry Truman’s Commission on Higher Education called for expanding higher education and making college at least partially free as far back as 1947. John F. Kennedy spoke of universal healthcare back in 1962. Someone living through this period must have easily imagined all of the aforementioned programs and sentiments transforming into more maximal versions of themselves: universal basic income, universal healthcare, the expansion of workplace democracy, full employment programs, and free secondary education, expanding in tandem with the ballooning economic prosperity America was undergoing on paper.

Unfortunately, that same someone would’ve been remiss and naive. In the aftermath of World War II, in light of these aforementioned programs and America’s relatively limited sacrifice during the war, the country was extremely well positioned to become a global hegemon. However much one believes New Deal Democrats to have been acting benevolently and in good faith, or if they perhaps were simply seeking to placate stirring masses whipped up by the Great Depression so as to prevent the US from having its own October Revolution, that fragile coalition and its vision was quickly dismantled and abandoned over the subsequent decades. Slowly but surely, the most reactionary forces have done everything in their power to reallocate America’s wealth towards an increasingly shrinking cohort of top earners. They have wrested power away from the working class towards an increasingly entrenched ruling class. As social programs stagnate or are culled, America’s military adventurism on the other hand never seems to have an issue procuring an increasingly fatter budget; the Pentagon appropriates nearly $1 trillion in funds annually in spite of never succeeding an audit, yet the so-called budget hawks are more interested in adding means testing (which in and of itself requires a costly bureaucracy) to existing programs like Medicaid in order to limit their spread and punish working class people.

Why have things been allowed to devolve in such dramatic fashion? Well, quite simply, there is nothing in America’s constitution, social fabric, or legislative policy protecting or enshrining these sorts of social welfare programs as human rights. Not long before his death, four-termer President FDR put forward a proposal to enshrine certain economic protections via a Second Bill of Rights. Though the language of the text was somewhat vague, if formalized and iterated upon with some legal backing, it could’ve imaginably been a step towards codifying New Deal governing posture more permanently. Instead, corporatists organized: they demonized foreign states which nationalized resources or ensured decent working conditions for their populations, as this threatened said corporations’ abilities to plunder the Third World. This led to American-sponsored “anti-communist” massacres across the Global South, from Indonesia to Guatemala, with casualties totaling in the several millions. Through McCarthyism, Red Scare propaganda, the “Southern Strategy”, and a coordinated decades-long campaign aided by intelligence agencies and politicians, they equated in the minds of the American public any vaguely egalitarian political reforms with the most exaggeratedly heinous qualities of existing socialist states and communist parties. Through the Heritage Foundation and the Federalist Society, they infiltrated Congress and stacked the Courts. They smeared any form of social welfare as being antithetical to enlightenment ideals of individual autonomy and “freedom” deeply entrenched in the American psyche. Through objectivist thinkers like Ayn Rand, neoliberal reformers such as the Chicago Boys, and their proxies across media and intelligentsia, they maximized “individualism” to the point of selfishness and self-isolation, and these social changes became manifest in every element of society: the dissolution of public transit was expedited, shared spaces have become increasingly prohibitive in cost and availability, people have taken on more isolating forms of entertainment and enrichment, a “hustle culture” which prioritizes one’s own economic stature over practically all else has gripped even America’s youth… American society has largely embraced free market libertarianism, and to what ends? The quantitative and subjective immiseration of the population: lower living standards, lowered access to basic necessities, more work for less money, and an increasingly isolated society. But we are supposed to believe that the ability to buy a spyware-loaded 4K TV for $300 represents progress. Even among some of America’s best and brightest egalitarian, socialist, and anarchist intellectuals, there often exists a tendency to distance oneself from collectivist thinking as a reflexive rebuke of hierarchy, totalitarianism, and past and present “communist” states. Our infrastructure, our communities, our pastimes, our intellectuals — all have been slowly veering towards increasingly isolating, self-centering modes of existence, and this was deliberately architected.

Understanding the Concentration of Power

That is why people who pronounce themselves in favour of the method of legislative reform in place and in contradistinction to the conquest of political power and social revolution, do not really choose a more tranquil, calmer and slower road to the same goal, but a different goal. Instead of taking a stand for the establishment of a new society they take a stand for surface modifications of the old society. If we follow the political conceptions of revisionism, we arrive at the same conclusion that is reached when we follow the economic theories of revisionism. Our program becomes not the realisation of socialism, but the reform of capitalism; not the suppression of the wage labour system but the diminution of exploitation, that is, the suppression of the abuses of capitalism instead of suppression of capitalism itself.

Rosa Luxemburg

So, if social safety expansions are by no means guaranteed, nor do they appear to eventuate in any sort of radical transformation of society or the economy towards more democratic or egalitarian ends (on the contrary: the only thing that seems inevitable is corporate-organized backlash resulting in repeal), how exactly should we course correct? Would codifying some protections against this sort of repeal in the law resolve the issue? Maybe, but without a constructive analysis of how power and wealth concentrates in American society and without a willingness to confront that dynamic, it would only delay the inevitable.

Let's break down the social dynamics which constitute our fundamental economic arrangements to understand where the incentive structures lie. Chances are, you, the reader, either work full-time, part-time, or you depend on someone who does. Your subsistence comes from a wage. Should that wage be cut off, perhaps you have a bit of a nest egg for rainy days if you are one of the lucky ones among us, but you would quickly find yourself in dire straits as your savings dried up. By this standard, you could be considered working class; you have to sell your labor for a wage in order to survive.

On the other hand, the CEO of your company (who is likely to make anywhere from 300 to 400 times your salary) has likely amassed significant wealth, so much so that they may even be able to comfortably subsist purely on returns from financial investments. If their company is public, they may be somewhat beholden to shareholders and a board of directors, but together, their dominion over your company’s labor and resources is near absolute outside of some limitations imposed by law to curb the worst excesses of exploitation. This makes them definitionally capitalists: someone who produces wealth by virtue of their capital, or their ability to buy assets which yield yet more money. In a capitalist society, this class of people represents the ruling class, the class of people responsible for setting social, cultural, political, and economic norms above all other social classes.

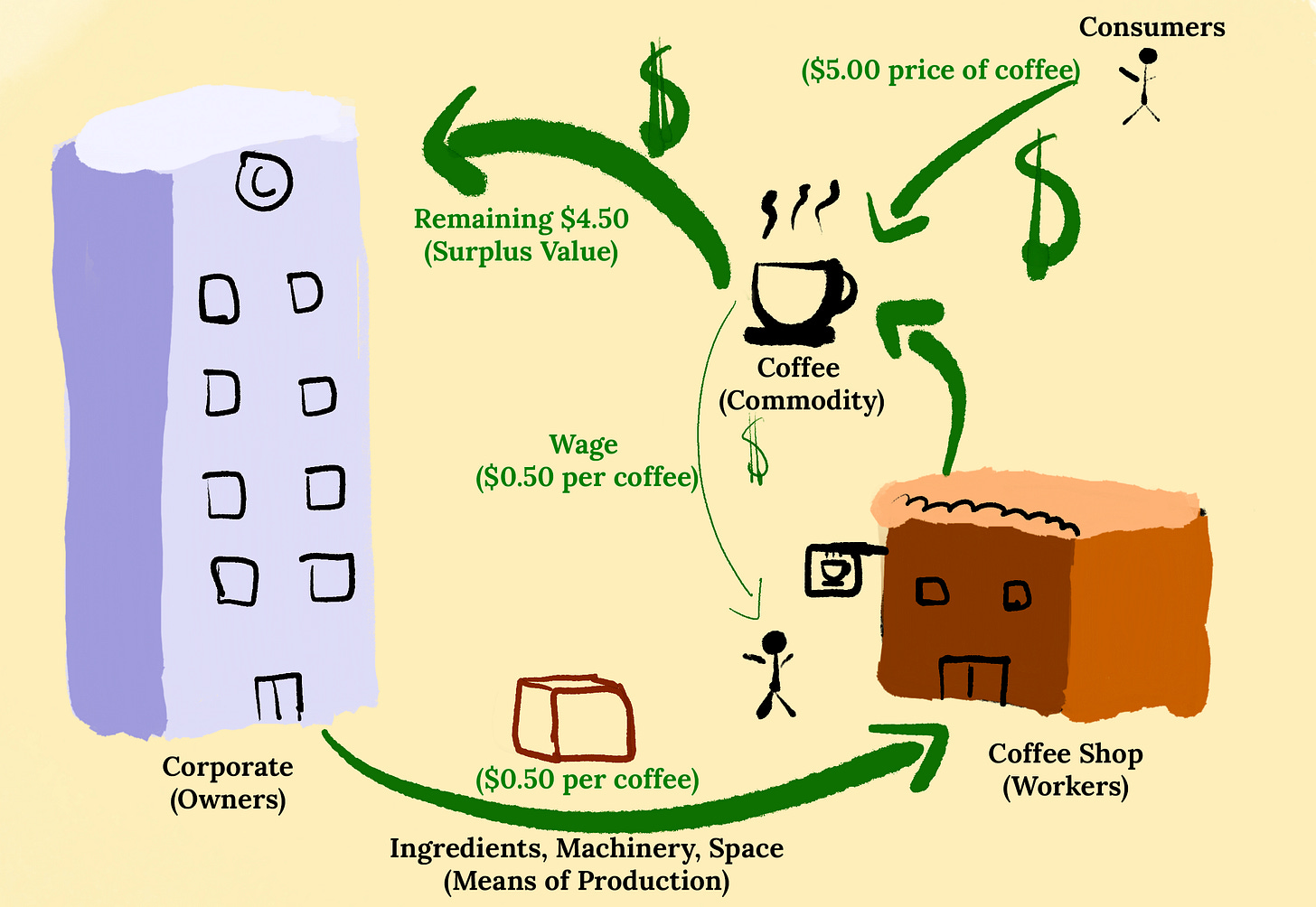

The social relation between you as the worker and your employers as capitalists is predicated on a delicate truth: the capitalists must be able to compel their workers produce more wealth from what resources they already have in order to perpetuate their own existence as owners. Let’s entertain for a moment that you are a barista at a large coffee chain. You have access to coffee beans, milk, syrup, and some equipment which can be used to make a cup of coffee, all of which were provided by your employer. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll say that all of the ingredients, equipment, storefront space, and marketing cost your employer about 50 cents per drink. You spend 5 minutes utilizing the equipment to produce a drink, and the customer is willing to pay $5 for it. You have just produced a commodity specifically for use in exchange. The extra cash, or surplus value, produced primarily through your work, or labor, is therefore $4.50 cents. In order for your employer’s firm to grow, they must pocket the majority of that extra value you just produced, either distributing it to the owners and shareholders as profit, or reinvesting it into the expansion of the business. If your employer were particularly generous by real world standards, they may take $4 and pay you with the remaining 50 cents.

In other words, as the Marxist economist and professor Richard Wolff likes to say, one might conclude that you are being ripped off! Even though your labor played a crucial component in generating an additional $4.50 in value from what was only worth 50 cents in means of producing coffee, you are only compensated with a wage representing a meager fraction of this new value. The owners of the coffee chain are not necessarily acting immorally, but could be considered amoral; they are simply engaging with a system of exchange predicated on this social dynamic. They must abide by the rules of said dynamic in order to persist and grow; otherwise, they risk fading into obscurity or being consumed by one of their competitors. Though the dynamic is laden with contradictions, the real moral quandary here is the lack of representation. For eight or more hours a day, our hypothetical barista resigns themself to be a subservient peon in this arrangement. They have no real protection or say in how the spoils of labor are distributed. From punch in to punch out, the democratic ideals which undergird our society become null and void. You are, in essence, renting one’s self to slavery, only free to skate between firms all subject to roughly the same logic, with varying degrees of arbitrary misery, for at least several hours a day.

Eventually, this coffee chain may grow and subsume its competitors one by one, as we have seen across industries in advanced capitalist nations. As corporations grow financially, their ability to command influence in governance and culture grows with them, but so too do the inherent contradictions of their very existence become heightened. How is one to continue expanding profits as their respective markets become saturated? Once you have sold a coffee to nearly everyone who can buy one every single day, what are you supposed to do to continue growing your profits at the same rate to appease your shareholders and owners? Find ways to get people to buy and drink more coffee? Sell coffee at higher rates and at lower quality and cost to the business? Or, maybe even eat into more of the space traditionally reserved for the public sector (think SpaceX taking on NASA’s functions, Palantir taking on the Pentagon’s role, or Uber taking on public transit). Writer Cory Doctorow has aptly coined this phenomenon “enshittification” — the tendency for businesses (especially online platforms) to entice people with compelling products, only to turn around and degrade them at the behest of profit seekers. With their newfound influence, they can lobby the state to play a vanishingly smaller role in our lives. This in turn creates a negative feedback loop, where the quality of services provided by the government degrades, and it therefore becomes easier to procure consent from the masses for the private sector to absorb more of the state’s responsibilities. And with these firms absorbing more and more of the responsibilities typically left to the state (though with incentives not generally rooted in public welfare but in the profit motive), we see higher costs and lower quality across all sectors for the average person.

What Is Socialism?

The analysis I have just articulated is not novel. Contrary to the empty bloviating of right-wing alarmists, this analysis laid out in our hypothetical scenario is just a massively abridged version of Karl Marx’s own analysis of capitalism. In fact, the vast majority of his work focuses on analyzing capitalism more so than any particular vision for how, when, and where whatever comes after comes about. Trained economists and financiers to this day study his analysis of capitalism for its fundamentally evergreen nature.

Marx was not a prophet, nor is he the sole authority on socialism. But the core conceit and his philosophical underpinnings are difficult to refute; he is simply observing that which is obvious under scrutiny. One may have encountered his philosophy of dialectial materialism: the idea that society is driven forward when groups of people seek to address the contradictions that always exist in social relations. For instance, the dynamic between feudal lords and serfs was transformed and dissolved with the emergence of the merchant class, which sought to usher in liberal democracy and capitalist markets.

Our aforementioned critique of capitalism paired with this historical and philosophical orientation should be the North Star for any self-described socialist. We have every reason to believe that the dismantling of wage slavery and ever-worsening and unsustainable exploitative social dynamics would be a mission that would resonate with the broader American public. The energy and resentment borne from the consequences of capitalism can be felt everywhere. Only a small minority of people feel engaged at work. Most recognize that electoral politics is largely bought and sold to the highest bidders. Americans are pessimistic about the future. But skilled orators and bold leaders need to be willing to embrace a more robust socialist narrative in the face of an emboldened and growing nativist, conservative, and perhaps even fascistic backlash, should they wish to address an ailing status quo.

Socialism, then, is not a set of reforms, nor is it necessarily characterized by the centrally planned economies of existing and past self-described socialist states. To be a socialist is to be doggedly oriented towards the abolition of the social dynamic at the core of capitalism, characterized by exploitative wage labor and commodity production, while pushing for the maximal democratization of the working class. It is the recognition that we can never have true democracy if the real centers of power, the owners of the market, can always consolidate wealth, influence, and power to not only control the lives of their employees, but sway even the state to do their bidding. To be a socialist is not to tinker with reforms, but to imagine and steward a future which dismantles these dynamics in favor of the expansion of democracy, freedom, and dignity, in government and in the market.

In this case, neoliberalism refers to politics favoring unregulated free market economics and a decline in government spending.