No One Is Coming to Save Us

Democrats' latest surrender is not an aberration, but the system working as intended. On the futility of waiting for moral politicians in a system designed to reward cowardice, and what to do instead.

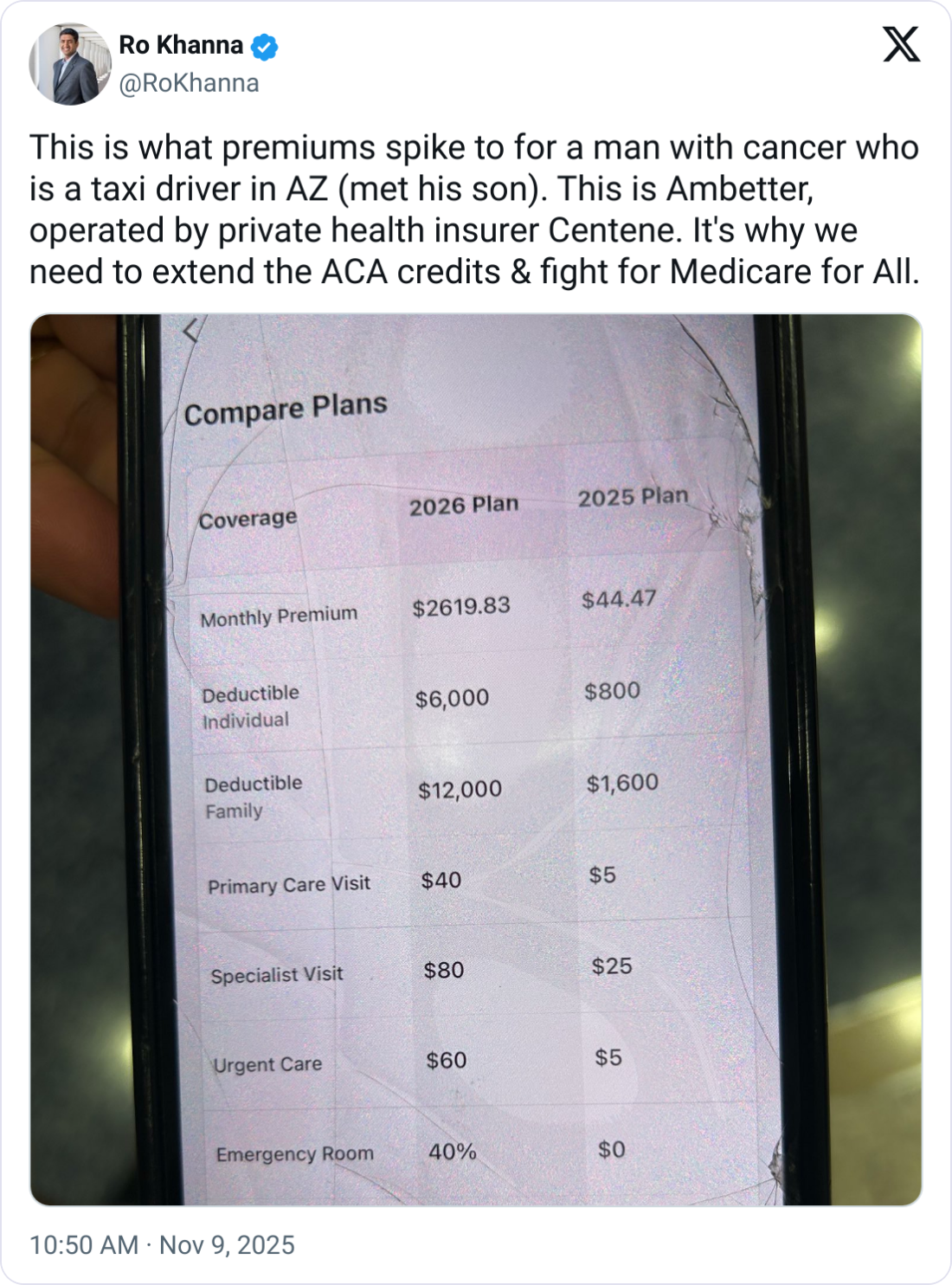

For the last six weeks, millions have been caught in the crosshairs of a political battle in DC, and Democrats may have just made it all for naught. In a nutshell, Congress must pass a budget every year by October for the upcoming fiscal year. Democrats put forward a funding bill which would extend Affordable Care Act subsidies, whose imminent expiration will likely spike nearly everyone’s health insurance costs. Reportedly, many of those most directly impacted could see costs double, triple, or even multiply many-fold in limited cases. Over the course of the shutdown, food assistance beneficiaries have been barred full rightful access to their benefits, and some may be starting to go hungry. Food banks across the country are being inundated and stretched. Additionally, millions of federal employees have been furloughed, either working without pay under the pretense that they will receive backpay upon reopening (a promise which Trump has threatened not to abide), or, as with many “non-essential” federal workers, being sent home without pay for the time being. Vital services, such as airline safety, are cracking under the pressure of understaffing at critical agencies like the FAA. Meanwhile, Trump has continued to sic his Immigration and Border Patrol agencies on undocumented and legal residents alike, ensuring that Homeland Security continues to enjoy ample funding and pay during the pause.

Late on Sunday night, reportedly with the blessing of Democratic Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, a Democratic “gang of eight” broke with the holdouts in their party to strike a deal with Republicans, rewarding them with the 60 votes required to proceed with temporarily funding the government. Most of these senators appear to have been hand-picked to minimize the political fallout: their reelection years are either too far into the future to matter, or they are retiring imminently. In exchange for capitulating, Democrats got a whopping helping of…virtually nothing. Well, technically, they got a promise to hold a vote on extending ACA subsidies separately in December, but that is almost certainly doomed to fail in our Republican-controlled government. A month of anguish and battle during the longest shutdown debacle to date was rewarded not with respite or concession, but with complete acquiescence. Angus King, one of the eight who voted with Republicans, put their fecklessness on full display: “Standing up to Trump,” he believes, “didn’t work.” To call this an opposition party to Republican excesses would be laughable.

When confronted with Republican opposition, Democrats have demonstrated time and again an inability to stand their ground. Meanwhile, progressive priorities and candidates are frequently sidelined and ignored, even when incredibly popular. Most establishment figureheads held out on endorsing Zohran Mamdani, who won the New York City mayoral primary all the way back in June, far longer than they had held out against their supposed political adversaries in this shutdown battle. Granted, the material stakes of indifference or opposition in that context are admittedly much lower, but that the purveyors of “Vote Blue No Matter Who” should so easily rebuke their own principles when faced with a candidate not of their choosing, while buckling under the weight of rightist demands in what was supposed to be a standoff for their constituents’ material demands demonstrates where their true priorities lie: the first priority is defeating progressive insurgency; opposition to conservatism and reactionaries is a second-order priority.

In the wake of ever-heightening hypocrisy and political frailty, even many Democratic Party diehards have begun to clamor for radical transformation from within, a hostile takeover via more youthful champions of platforms more emblematic of the sorts of anti-corrupt, socially democratic reforms America’s youth seems to be gravitating toward. There are also those calling for a clean break from the Democratic Party and the construction or bolstering of a new third party.

Barring the clear and obvious structural impediments to such ambitions, both initiatives I think misunderstand or underestimate the systemic, structural pressures which have given rise to the current predicament. Even assuming it were possible to garner significant power via a third party or by reforming the Democratic Party from within, we would likely quickly find ourselves in a similar place without key institutional advancements made within and especially without the expressly political realm. No matter what lies in any unique politician’s heart, they are ultimately in aggregate subject to the rules of the system they inhabit. Studies of “opportunistic behavior in local government policy decisions” and “electoral opportunism” empirically demonstrate that politicians routinely adjust policy not to ideals but to electoral calculus, a logic visible even in Washington’s shutdown brinkmanship. Decades of public-choice research reinforce the uncomfortable truth that intentions are structurally irrelevant when incentives run the other way. The Powell Memo of 1971 merely accelerated a preexisting trend: the consolidation of political power through capital and class coordination. From the 1970s onward, corporate lobbying expenditures ballooned from millions to over $3 billion by 2023, and union density collapsed from over 20% to around 10%. Those shifts did more to redefine the incentives of both parties than any ideological awakening could.

Regardless, the entrenchment of political power in an upper class has long been a constitutional component of the political character of liberal democracy; despite its own contradictions and aspirations for equality, recall that this is a political system which often puts the sanctity of private property above life itself, which, until recently, gave sanction to the ownership of fellow human beings demarcated along arbitrary racial lines. 20th century advancements in social welfare were only made possible through institutional threats: unions, maximalist political parties, and activist groups, as well as the threat of revolution laid bare in socialist uprisings the world over. In simpler terms, political leverage once derived from organized capacity to disrupt production. As the Swedish sociologist Walter Korpi articulates in The Democratic Class Struggle (1983), the welfare state emerged not from electoral generosity but from the credible threat posed by militant labor. In the mid-20th century, over a million workers struck annually in the U.S. By 2022, that number had fallen below 120 thousand. The erosion of unions and socialist parties has left no comparably organized force capable of disciplining capital, nor, by extension, the politicians who depend on it.

Obviously, these imperfect vessels were wrought with their own sets of problems, some of which we are still experiencing today: union leaders continually fail to hold political parties to account including with this latest shutdown fiasco, and, as alluded to earlier, union membership continues to decline, despite the recent wave of positive sentiment. But in their ashes, modern alternatives have not yet been able to fully materialize. What it means to organize effectively is to build publicly accountable institutions distinct from government which wield the capacity to grind the gears of economic production to a halt if need be. Business leaders, in part by virtue of their vertical organizational structure and consolidated decision making powers, have been incredibly organized among themselves and have wielded their immense wealth to assuage political outcomes. Without this very same sort of material leverage, which political party occupies the halls of power matters little. Though voting remains an obligatory expression of political dissent, we must avoid mistaking it for complete power. In the absence of countervailing institutions (unions, cooperatives, mutual-aid networks, or some yet-to-be-built federated movements capable of disrupting economic normalcy) politicians will continue to be caught in the gravitational pull of capital and bureaucracy. The task, then, is not merely to elect better people, but to build better constraints under which even opportunists must behave on account of the public welfare.