Debt Radicalization

Realizing that the budget hawks are wrong about almost everything can serve as a solid first step towards embracing a more compassionate economic and governing posture.

For decades, politicians have cast social spending as a Sisyphean task, each dollar pushing us closer to collapse. Whether peddling modest reforms seeking to mildly meliorate the lives of poor and working people, or pitching a radical sea change oriented towards the dismemberment of systems of wealth accumulation built on doling out paltry wages and near-to-slavery working conditions across the non-Western world, one will surely be lambasted with the seemingly age-old, loaded, rhetorical gotcha question: “How are you going to pay for it?” We have been made to accept the idea that the budget of a state could be analogized to a household budget, and as a result, certain social spending is not deserving of our financial commitment. Those youths facing increasingly insurmountable student debt obligations or the 66% of bankruptcy victims that report being smothered by medical debt are apparently shit out of luck. The question of how we are going to pay for things is conveniently never seriously posed against military spending, corporate subsidies, or financial bailouts for banks.

Many readers of mine are likely privy to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), the countercultural economic framework which fundamentally challenges the aforementioned dominant notion of government budgeting entirely. For those not in the know, the main thrust of MMT is that governments are not financially constrained in the same way as households are, because governments, through one mechanism or another, wield (and often exercise) the ability to influence the circulation and amounts of dollars in the economy. Thus, government deficits are better thought of as investments in different segments of the population and the productive forces of the economy rather than spending in the traditional sense. This has especially been true since 1971, when President Richard Nixon took the final steps towards eliminating the gold standard, unlinking the dollar from the value of gold. This process completed an ongoing transformation of the U.S. dollar into a fiat currency, or a currency whose value is not backed by or predicated on any tangible or finite thing.

If one wishes to bolster our understanding of MMT, a great starting point is none other than one of MMT’s most prominent proponents in Stephanie Kelton. In her book, The Deficit Myth, Kelton deftly dispels orthodox economic edicts about government budgetary balancing and instead offers up a more human-centered budgetary proposal. The government running a deficit, she argues, simply means that more dollars are being placed into private hands than the government is pulling back out of circulation via taxes. Where and how this money is being supplied to the economy is more consequential than how much of a deficit the government runs. For instance, it is easy to imagine how dollars allocated towards certain social services and public welfare could actually produce an anti-inflationary effect, if it meant that it increases the supply of some inelastic or necessary product. If, for instance, the government focused its spending on building more housing, this may run up the deficit in the short term, but the productive capacity of the newly required labor to build said houses, the expanded tax base, the increase in supply of housing, and the stability and opportunities this would impart upon the residents of these new houses would all confer positive social and economic benefits. Taxes, then, are not (and really never have been) a means of funding government services; rather, they exist to cool and manage economy, by creating demand for currency, balancing wealth inequality, and controlling inflation. New money is instead primarily created through forms of credit. Banks can issue loans for money that doesn’t yet technically exist. The Federal Reserve can exercise several powers, like the manipulation of interest rates and the buying and selling of bonds and securities, to stimulate banks to either create more or less money.

In simpler terms, our modern economic framework is heavily rooted in systems of credit and debt. But, contrary to economic tropes about the evolution of human exchange, this dynamic is not unique to contemporary economics. Debt can instead be understood as the bedrock of all exchange. In his book, Debt: The First 5,000 Years, anthropologist David Graeber compiles a thoroughly examined corpus of historical evidence in support of exactly this notion. He opens the book opining on the the tacit moralism of debt. He recalls an interaction with an individual working at a non-governmental organization who expressed dismay at the idea that recipient nations of predatory loans offered by the International Monetary Fund should have their debts forgiven, with this person remarking that there exists a moral obligation to pay back one’s debt. Throughout the rest of the book, Graeber artfully intertwines this moral precedent with the main thesis of his book. Conventional wisdom would have you believe that trade and barter economies gave rise to cash-based economies, which eventually evolved into credit-based forms of exchange. But according to Graeber, this story isn’t well substantiated by anthropological evidence nor even intuition. He instead argues that the concept of debt itself is a basal social phenomenon, and its adherence can be compelled by social trust, violence, or moralistic storytelling. The creation of money therefore is just an attempt at objectifying already existing notions of value; rather than owing somebody some vaguely equivalent service or favor in the long term in exchange for receiving something from them, money was born to assign concrete numerical values to these exchanges. In this sense, money could be understood from its conception to be a form of circulating IOUs.

Throughout the book, Graeber contrasts examples of what he coins as “human economies”, or economies predicated primarily on relations between people rather than commodity allocation that we often see in remote societies or historical societies, with modern economic arrangements that are oriented around commodity production. He traces a direct line from the Axial Age economies of ancient civilizations, through the feudal world of the Middle Ages, right up until the industrial revolution, the birth of capitalism, and the modern era of credit-based economies built upon virtual currencies. He hearkens back to practices of debt forgiveness as a means of rehabilitating social stability in ancient times, such as we see in the biblical jubilee. He parallels the intrinsic relationship between debts, war, and taxation that existed even in ancient societies like Greece and Rome which often gave rise to slave complexes, to the West’s ability to effectively enslave the Global South through similar arrangements today. And he warns of debt’s ability to be taken to dark places: the reduction of human beings themselves to quantifiable stores of value. Ultimately, Graeber arrives to very much the same conclusion as Kelton: debt is to be understood as an instrument of social welfare, and limitations on our ability to have, do, or produce commodities and services is rooted in the material realities of production, not arbitrarily determined budgets. The United States already exercises this muscle: because nearly all economic activity is tied to the U.S. dollar by virtue of the country’s global economic hegemony enforced primarily through militarism, debts that the U.S. owes to other countries can roll over seemingly indefinitely. Yet, so long as the U.S. owes debts to these nations, America’s interests become intertwined with those of its creditors, since these countries are effectively investing in the U.S. economy by crediting it.

Through the various alternative systems of exchange and historical concepts highlighted in the book, Graeber seeks to compel people to think beyond typical myopic preconceptions around money, wages, and the economic arrangements of capitalism. Chartalism, the notion that the markets, money, and the state are all inextricably linked, if well articulated, can be a powerful tool for unlocking the collective imagination of the masses to think of money and exchange in new and liberating ways.

I can speak for myself: beginning to understand the nature of the national debt was integrally radicalizing for me. As a teenager, I was not particularly politically engaged, but I was adherent to broadly libertarian social conceptions. My personal political philosophy didn’t extend much further than, “I don’t care what you do, so long as it doesn’t infringe upon me,” and I was largely bought into mainstream views around government budgets being akin to checking accounts. I would suspect that a lot of Americans likely fit a similar, somewhat politically diametric mold.

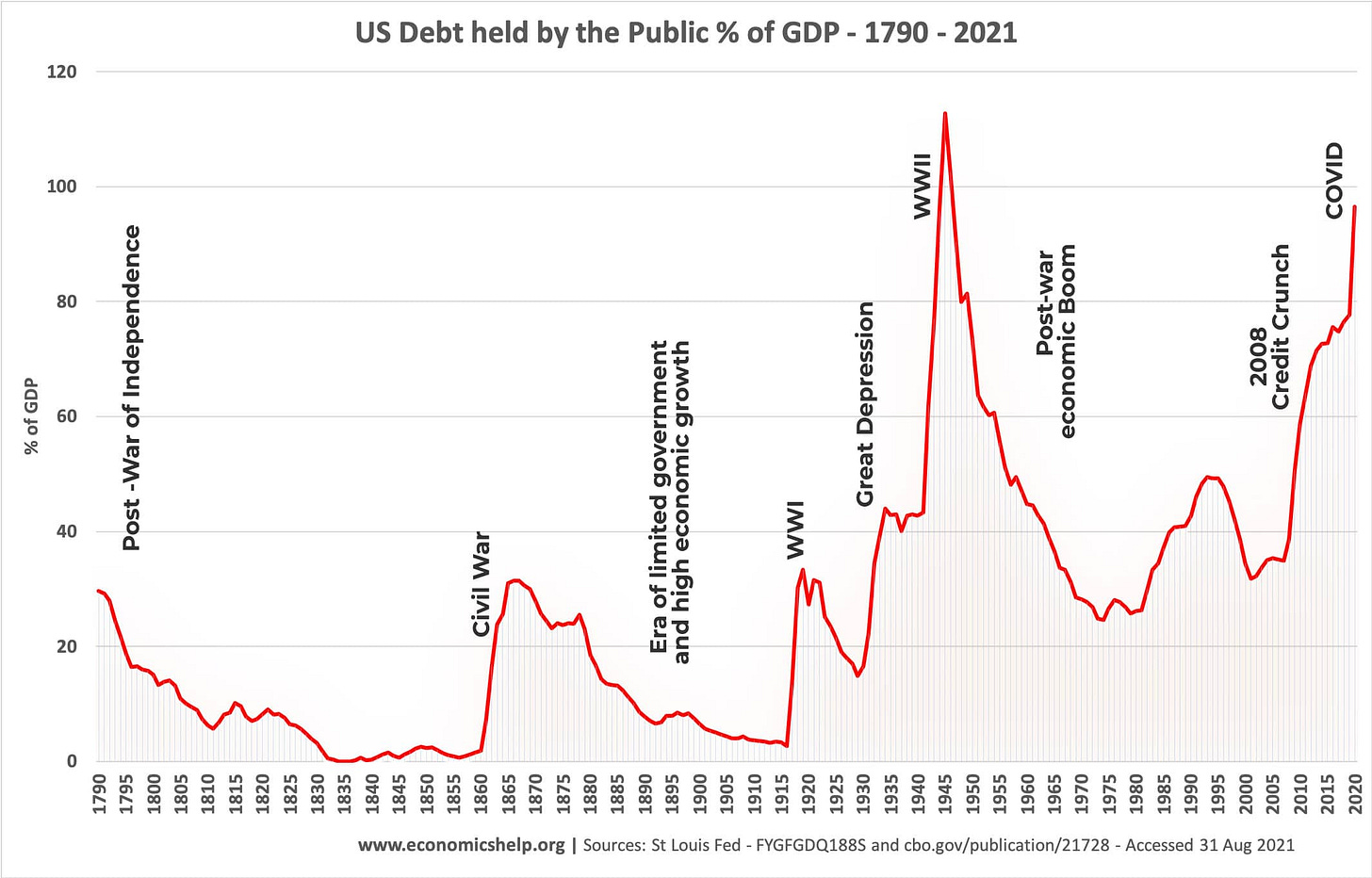

Growing up the child of Middle Eastern immigrants from countries torn asunder by American imperialism, I always had something of an anti-imperialist streak, and this certainly played a role in the evolution of my own politics. However, my understanding of domestic politics and my preconceptions around economics had really begun to be shaken when I became more learned about the American social programs of the 20th century, their ambition, scale, and rigor, and how they have not really evolved (or have even been pared back in many ways) despite tremendous increases in productivity. Naturally, I was beginning to wonder why and how this could be the case. Then, I vividly remember when the dam really began to crack: when I encountered this (now slightly outdated) graph:

In interpreting this graph, I began to intuit something that was later made concrete when I read from thinkers like Graeber and Kelton. In the period from 1933 to 1969, the country enjoyed a massive expansion of social safety programs, and it expanded these programs and rights to greater and greater numbers of people: those marginalized communities who were beginning to enjoy new protections via civil rights legislation and the exploding population of the baby boomer generation. And yet, contrary to the paranoid musings of today’s deficit hawks, the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio experienced a net decrease over the same period, and the period following World War II is in many ways seen as the pinnacle of American prosperity.

It should go without saying that this period was not all sunshine and rainbows, and I don’t mean to minimize the obvious moral stains of the era. America’s neocolonial resource extraction machine went into overdrive over this same period, which almost certainly influenced some of this positive growth, and minorities were fighting an ardent battle for equal rights. But still, it’s hard not to look at this data and not see in it sheer evidence of MMT’s main crux: allocating more money and attention towards social betterment doesn’t necessarily have to entail unsustainable levels of debt. How and where the government runs deficit spending is a conscious choice: one rooted in the interests and incentives of the ruling class, which, in our society, happens to be landlords, corporatists, executives, and shareholders. Making this plain for the layperson to understand can be a crucial first step towards building consciousness for new and truly liberating modes of economic arrangement.

In any case, before long, the average person will be forced to examine their own relationship with debt, if they haven’t been already. Increasingly, we are made to be effective debt peons. We must take on increasingly burdensome loans that we can never repay. Student loans go on for decades, medical bankruptcies are commonplace, and transportation in this country often demands ownership of a multi-thousand-dollar vehicle and all of the associated costly maintenance. Personal ownership of basic necessities like housing is becoming a prospect increasingly out of reach for an increasingly larger group of people. We are increasingly becoming subjects to rentiers, victims of debts and rents we can never fully repay: subscription services, lifelong housing rentals, insurmountable loans... and when one is beholden to debts they can never repay, they effectively become slaves. But this was always the logical endpoint of our current economic trajectory. As Graeber put it:

To what degree is [slavery] actually constitutive of civilization itself?

I am not speaking strictly of slavery here, but of that process that dislodges people from the webs of mutual commitment, shared history, and collective responsibility that make them what they are, so as to make them exchangeable-that is, to make it possible to make them subject to the logic of debt. Slavery is just the logical end-point, the most extreme form of such disentanglement. But for that reason it provides us with a window on the process as a whole. What's more, owing to its historical role, slavery has shaped our basic assumptions and institutions in ways that we are no longer aware of and whose influence we would probably never wish to acknowledge if we were. If we have become a debt society, it is because the legacy of war, conquest, and slavery has never completely gone away. It's still there, lodged in our most intimate conceptions of honor, property, even freedom. It's just that we can no longer see that it's there.

We have a choice to make: we can continue down this path, or we can evolve beyond a mode of commerce which always seems to reduce human beings to calculable stores of value.