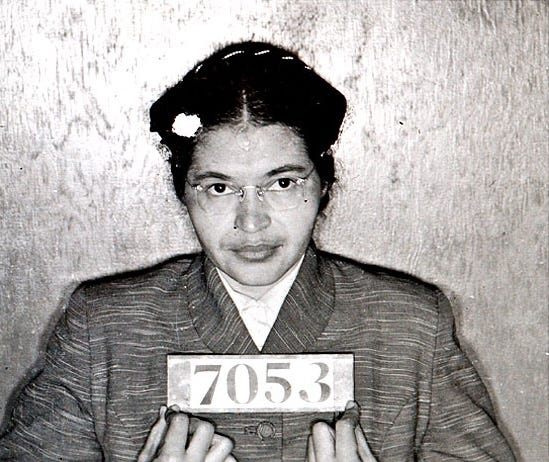

Carrying on Rosa Parks' Militant Activism

Behind the watershed incident that has made her a legend in the American pantheon: a life of oft overlooked radical activism. Like Parks, we must organize to further transit equity.

Four years ago today, on what would be Rosa Parks’ 108th birthday, then-Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg sought to honor her legacy by committing to upholding transit equity. In the years that ensued, transit agencies across the country began observing the new day under various labels: Transit Equality Day, Transit Equity Day, and Rosa Parks Day.

Though our understanding of Parks is often constrained to the moment of protest that lit the spark behind the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Parks lived a life characterized by radical activism. And while the boycott she was responsible for instigating led directly to the Supreme Court decision that made bus segregation illegal, a car-oriented United States, carved up by highways and redlining, has left many in poor and rural communities without decent access to transportation to this day. Thus, much work remains to be done before we can truly celebrate “transit equity”. We can draw inspiration from both Parks’ life and the successful mass action campaigns she inspired to think about where to go next.

Parks’ Upbringing in Segregated America

“Such a good job of brain washing was done on the Negro that a militant Negro was almost a freak of nature to them, many times ridiculed by others of his own group.”

Born in the era of Jim Crow and racial segregation, Parks was forced to confront racial injustice practically from day one. In response to black soldiers returning from World War I, the Ku-Klux Klan exercised a widespread lynching campaign on black communities. A 6 or 7 year old Parks wrote of joining her grandfather (a supporter of the Pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey) for late nights on the porch, armed and ready with his shotgun to defend the house from potential racist agitators.

By eighteen, Rosa met both the man she would eventually marry and her entryway into political organizing. Raymond Parks, a young barber, was working within the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to organize legal defense for the Scottsboro Boys, a group of black teenagers wrongfully accused of rape. Unfortunately, all but the youngest were ultimately sentenced to death. Amongst their most ardent defenders were communists, whose meetings Rosa and Raymond subsequently attended.

In 1943, twelve whole years before her paramount encounter, Parks had a separate run-in with a bus driver. After paying, the driver instructed her to exit and re-enter the bus through the back door, as was standard practice for black people in Montgomery at the time (amongst other arbitrary seating arrangement rules intended to segregate black people). Rather than wait for her to enter via the back, the driver simply drove away, stranding her at the stop. Parks vowed never to board his bus again. She later lamented more broadly, “You died a little each time you found yourself face to face with this kind of discrimination.”

That very same year, Parks joined the NAACP. She sprang into action alongside union leader E.D. Nixon to pressure the Montgomery chapter to take activist positions against Jim Crow. Mentored by the socialist civil rights leader Ella Baker, Parks focused primarily on anti-rape and anti-lynching cases. Over the course of the next decade, with Parks in league, the Montgomery NAACP carried out mass voter registration campaigns and put school and bus desegregation at the center of its platform.

During that same period, multiple escalations between black people and police on the bus ensued, eventually culminating in Parks’ fateful act of protest. In 1944, Viola White was arrested, beaten, and fined for refusing to surrender her seat. In 1950, Parks’ neighbor, Hilliard Brooks, was killed for refusing to give up his seat. In 1955, a 15 year old Claudette Colvin was arrested for resisting being manhandled off the bus by police. Finally, just days after the men who lynched 14 year old Emmett Till were acquitted (whose death became posthumously iconic in the Civil Rights Movement), Parks, now a consummate organizer with years under her belt and frustrated by the outcome of Till’s case, refused to give up her seat, eventuating in her arrest. In a twist of irony, the driver who had ordered her to vacate her seat was James F. Baker, the very same driver she had encountered over a decade earlier who stranded her on the street even as she complied with his orders. Later on, in her autobiography, she wrote, “[The] only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

“Integrating that bus wouldn’t mean more equality. Even when there was segregation, there was plenty of integration in the South, but it was for the benefit and convenience of the white person, not us.”

Park’s arrest sent Montgomery’s network of activists over the edge. Jo Ann Robinson and others from the Women’s Political Council got to work, printing and distributing thirty thousand leaflets stating, “Another woman has been arrested on the bus.” Black people across the city got to organizing the boycott, supplanting the bus service that so many were previously dependent on with their own ride service. At its peak, the Montgomery Improvement Association was coordinating ten to fifteen thousand rides a day. Just over a year later, the Supreme Court ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional, ending the successful bus boycott.

Though Parks had been instrumental in bringing about significant justice to Montgomery, her newly marked reputation had made her and her husband something of a pariah. Within weeks, the pair was unemployed and were being increasingly made destitute. Seeking new opportunities, they made their way up north to Detroit, where Parks would continue fulfilling a rich life of humanitarian activism. Parks cited prominent civil rights figures like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. as her heroes, attended Black Panther schools and conventions, fought for reparations, opposed the war in Vietnam, and, to really bring home her political relevancy today, even publicly opposed the appointment of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court.

The Northern Promised Land That Wasn’t

To Parks, the state of civil rights in her new home up north betrayed the North’s reputation. Upon arrival, she called it “the Northern promised land that wasn’t”, and expressed discontentment with the level of segregation, discrimination, and police brutality she witnessed. Even in the years that followed, though black people and minorities would eventually secure voting rights, and segregation would be outlawed, racial imbalance along poverty lines and the uneven application of criminal justice still exist to this day as echoes of Jim Crow, slavery, and redlining. But perhaps more relevantly in this story, an America that has spent the last century in full swing towards car dependency has ensured that access to transportation is anything but equal or equitable.

With lesser access to automobiles due to their prohibitive costs, impoverished groups (and by extension, often minorities, who overrepresent here) require greater access to public transit in order to access essential services and resources. Simultaneously, even in urban contexts, these groups also tend to occupy spaces in which access to public transit and even those very same aforementioned essential services are weak compared to higher-class neighborhoods. Additionally, the sprawling suburban development that has been brought about by the proliferation and supremacy of the automobile in American culture (which was, in part, spurred by white people fleeing newly integrated metropolitan areas), and our government financially bankrolling and perpetuating this reality to the tune of 5 times that of alternative transportation infrastructure, has deteriorated our social fabric by isolating us and is compelling cities to build out into unsustainable debt traps, sending many such cities into bankruptcy.

In many ways, the segregation that Rosa Parks experienced on that bus has been foisted unto broader American society along class lines. Those of us with the luxury to drive can self-isolate in our rolling metal cages, while others less fortunate either plunge themselves into financial ruin to become debtors to the steep and increasing costs imposed by the profiteers behind the automotive and oil industries, or they relegate themselves to alternative or public transit options, which, thanks to aging and neglected infrastructure and sprawl, is usually either infinitely less accessible and convenient or more dangerous. To guarantee truly greater equality in transit, we must demand from our governments, both local and federal, the sorts of reforms and investments that would lower housing costs, connect neighborhoods, and serve those who desire to be or are compelled to be car-free: social housing, rent control, zoning reform to facilitate greater density, and most importantly, massive investment in engineering and building our cities to be less car-oriented. At this late date in the development of the country, it may seem hopeless to try and reverse a hundred years of suburbanization and sprawl, but popular sentiment is shifting, and perhaps we can draw from Parks’ own activism to pressure advocacy groups and orchestrate successful campaigns much like the boycott her own civil disobedience inspired. In her own words: “Don’t give up and don’t say the movement is dead.”