America's Role in the World's Largest Humanitarian Crisis

Though Sudan's latest catastrophe is largely reflective of an internal power struggle, the grounds and ammunition for the current turmoil were laid directly and incidentally by the West.

Sudan has known nary tranquility since its inception in the 20th century. Like much of the Global South and East, its borders were imposed upon its people arbitrarily by the Western colonial powers that be. The current civil war, which began in 2023 after numerous failed attempts to replace the military junta, which rode popular consent to usurp the prior dictatorship, with a civilian-led government, has crippled its populous and subject them to abject, torturous conditions. 24.6 million people are facing acute food insecurity, while 637,000 are facing catastrophic levels of hunger according to the World Food Programme. As of January this year, the Preparatory Committee of the Sudanese Doctors Syndicate estimated that over 500,000 children alone have died due to malnutrition. The UN Refugee Agency estimates that 13 million people have been forced to flee as of April 2025.

Immediate Ways to Help

Reputable Charity & Mutual Aid Organizations (Donate)

Organizations on the ground serving those impacted by famine and displacement are in desperate need of funding and aid. You can donate to some of these listed below.

HRRDS (supports disabled and vulnerable populations)

Hope and Haven for Refugees Association

Follow Activists

Following accounts, including but not limited to those listed, can keep you up-to-date with the situation on the ground.

Raise Awareness

Bringing international awareness to the ongoing crisis and the West’s complicity in it can sway more groups and organizations to get more journalists, cameras, and aid on the ground, as well as bring people of conscience interested in peace to rally behind political causes aimed at blocking the flow of munitions.

But this war, for all of its horrific excesses, is simply the latest chapter in a series of humanitarian disasters spanning decades. The country has experienced coup attempts every decade for the last 60 years and suffered two protracted civil wars prior to this latest rendition that also saw millions killed and millions more displaced, starved, and injured. From the very moment that the state went independent from British colonial rule, it was functionally destined for conflict, thanks to the designs of its former colonial masters. In employing their tried and tested “divide and rule” strategy, the West intentionally stood up two parallel societies in the northern and southern parts of the country so as to undermine the conditions for anti-colonial unity. In the more Islamic, Arabized north, British leaders fostered a robust slave trade via their Arab proxies that led the Christian-led south to resent their northern counterparts. Thus, from very early on in Sudan’s existence, the less characteristically Arab south, where the majority of fertile land and commercially viable resources (including and especially oil) resided sought to secede from the Arab-dominated north.

The dawn of Sudan’s independence in 1956 coincided closely with the dawn of the post-World-War-II international order that, over the coming decades, would entrench the US as the world’s sole hegemon. In the infancy of the US’s global supremacy, it had taken on the work of continuing Britain’s colonial project in Sudan, embarking on a decades-long project to create an oil vassal in South Sudan by supporting rebel secessionist groups in that part of the country. Over time, this effort materialized via USAID programs, military training for secessionists like John Garang (who led the creation of the People’s Liberation Army and played a central role in South Sudanese secession), and propagandizing via NED-funded outlets. The US simultaneously imposed sanctions on Sudan from 1997 to 2017, alleging connections to terrorist groups on false or shaky pretenses. In 1998, President Bill Clinton ordered the bombing of the then-recently-constructed Al-Shifa major pharmaceutical factory based on allegations (which were later debunked) that the plant was a covert chemical weapons facility for Al-Qaeda. The bombing ultimately deprived the young country of a critical piece of medical infrastructure. 50% of the country’s pharmaceutical production capacity was crippled, exacerbating public health crises such as with malaria. All of these efforts to destabilize and divide the country ultimately culminated in a lopsided ballot referendum in 2011 which saw the creation of South Sudan, currently still the world’s youngest state.

While the nascent country of South Sudan is rife with its own set of internal disputes, the sudden detachment of a major facet of the original country’s wealth exacerbated economic problems up north. In 2019, widespread demonstrations eventuated in a military-led coup of Omar al-Bashir, who had reigned over Sudan for 30 years. Civilians quickly demanded that power be transferred to a civilian-led government. Initially, their calls were met with violent reprisal; the military responded to a sit-in at their headquarters in Khartoum by executing over 120 people during the holy month of Ramadan in what could only be described as a massacre. A few months later, an agreement was reached between the military bodies that ruled the country and a civilian-led council to slowly transition towards a fully civilian-led government.

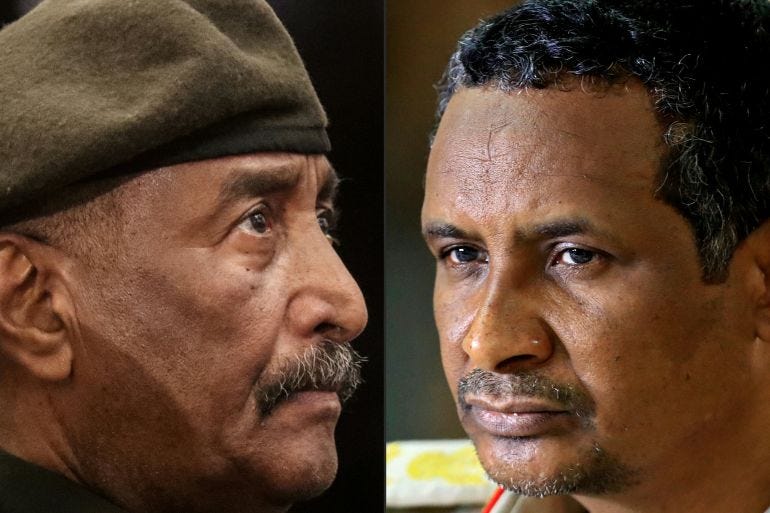

But this agreement, and the various revisions of it that followed, were inherently brittle right from the start. The power sharing agreement was really between three rather than two parties: Sudan’s official military (Sudanese Armed Forces) (SAF), a paramilitary force known as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) sprung from Arab tribes, and the civilian council. The RSF, originally known as the Janjaweed militia, was formed by former dictator Omar al-Bashir to wage a genocidal proxy war in the early 2000s not so dissimilar from the current crisis. Hemedti, the current leader of the RSF (of whom little is known), climbed the ranks of the organization. The RSF became increasingly prominent, imposed control on gold mines to bolster their own funding, and curried favor with major powers. Operations to curb migration to Europe bolstered their relations with Western powers, and both the RSF and the SAF participated in the Gulf states’ genocidal campaign in Yemen, bolstering their relations with the very same states who would later fuel the current crisis through arms supply. At the same time that the aspirational Hemedti ascended to lead the RSF, a man named Abdel Fattah al-Burhan became the leader of the SAF. He, too, was often unkind to the ethnically black populous of Darfur, crushing rebellions over the years.

Al-Burhan and Hemedti coordinated the military-led government from 2019 to 2023. Tensions over the future of the country boiled over in Ramadan that final year, leading to the beginning of the catastrophe and the current humanitarian crisis in the Darfur region. The main points of contention were over how long the transition period to the civilian government would be, and how the RSF would be integrated into the SAF. Both topics of consideration ultimately threatened to diminish the power that Hemedti had accrued and enjoyed over the years, reducing him and the RSF and subservient entities to the other two parties.

Since the beginning of the conflict, it has become evident that the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia, major beneficiaries of American arms and financial support, have been supplying the RSF and SAF respectively with advanced weaponry, exacerbating the scope and scale of the conflict. I have scoured OSINT channels and have surprisingly found scant evidence that any of the weapons that have made their way into the hands of the combatants originate from American defense firms. However, one can assume that, if America continues to bolster the UAE and Saudi Arabia with arms, then the two nations can consequently offload surplus arms from other arms dealers, including those operating in China and Russia, to their proxies in Sudan. Evidence of such has been extensively demonstrated by journalists operating within the region. In effect, the Gulf monarchies are waging a proxy war over the fate of Sudan’s future and control of Sudan’s abundant gold and agricultural resources.,

In spite of handwringing and resolutions put forth by Congresspeople, the United States continues to sell billions in arms to the UAE and Saudi Arabia. The West must exercise the greatest source of leverage it has and stop providing arms to the Gulf states unless and until they stop fueling the crisis in Sudan (and, on a separate but related note, Yemen). Shortly after Sudan’s inception, the country became a dumping ground for weapons, with the US selling about $1 billion in arms to the fledgling state during the Cold War—a reality which has persisted to this very day. That fact, paired with the tensions created by colonial intervention, has set the stage for half a century of violence, killing, famine, and instability in both Sudan and its offshoot in the south. Terminating the flow of arms to opportunistic actors looking to exploit the turmoil and expand their control over the country won’t solve all of its problems overnight, but it would be a solid first step towards the lasting peace its people deserve after centuries of intervention.