AI Will Create More Bullshit Jobs

Unless workers have a say in distributing the benefits of automation, the societal reconfiguration Sam Altman has prophesied likely won't come. "Bullshit Jobs" can help us see why.

Since the advent of ChatGPT, artificial intelligence fervor has swept Silicon Valley. Its champions have been singing its praises, making ostentatious claims about how imminently it will usher in a sociological renaissance through artificial general intelligence (AGI). And the money has followed, flowing into companies like Nvidia, Palantir, and OpenAI at the center of these grandiose promises. Sam Altman, the founder of OpenAI (the firm behind ChatGPT), has long suggested that AGI is around the corner and has shifted goalposts accordingly. Last month, he stated in an interview that he expects that AI to bring about “some change required to the social contract,” and that the whole of society will be “up for debate and reconfiguration”. Silicon Valley magnate and major Trump donor Marc Andreessen recently suggested that AI will soon replace middle management. Elon Musk has long painted an apocalyptic vision of AI’s future, once likening AI research to summoning demons and more recently suggesting a non-zero chance AI “goes bad”, playing to some horror fantasies about some rogue, Skynet-like catastrophe.

Contrary to the elaborate musings of AI’s top connoisseurs, research is already beginning to suggest that our current methodologies for training these models are beginning to apex and plateau. While minor breakthroughs and adjustments have continued to open up new capabilities and improve the accuracy and performance of these models, and while I do personally believe that there yet remain many potential, untapped creative use cases for these models, lofty assertions about some general superintelligence seem to so far be more like farfetched sales pitches to the venture capital class, intended to justify the trillions of dollars propping up an industry predicated on speculative hype, rather than true prophecy. And personally, I’m not too keen to have corporate figureheads like Sam Altman be the ones at the fore of the debate over social configuration.

All of that being said, even if we grant that some work is likely to be automated in some fashion as these tools advance, we have several centuries of industrialization and an exponential rise in automation to look back upon that can serve as strong indicators for where things may go, with no real reason or evidence to believe that these new breakthroughs will culminate meaningfully differently. All the way back in his 2018 book, the late anthropologist David Graeber articulated a useful analysis about the contemporary state of work that may wind up being prescient.

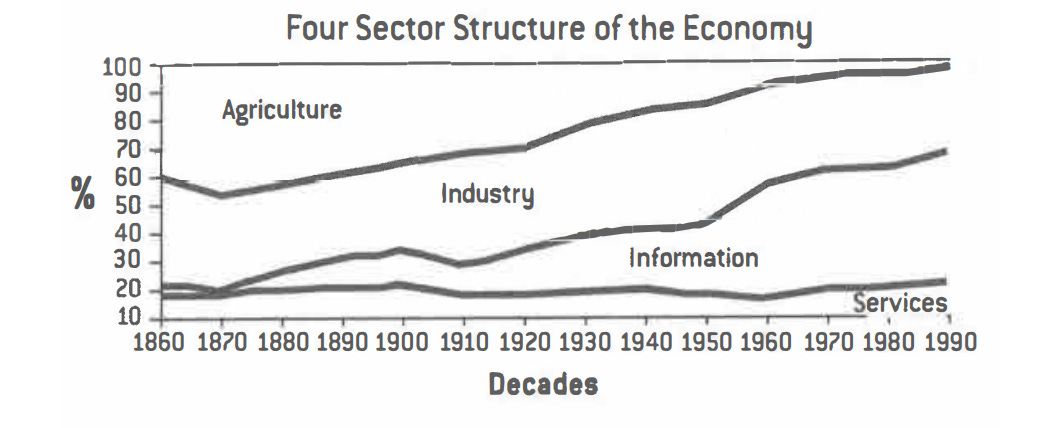

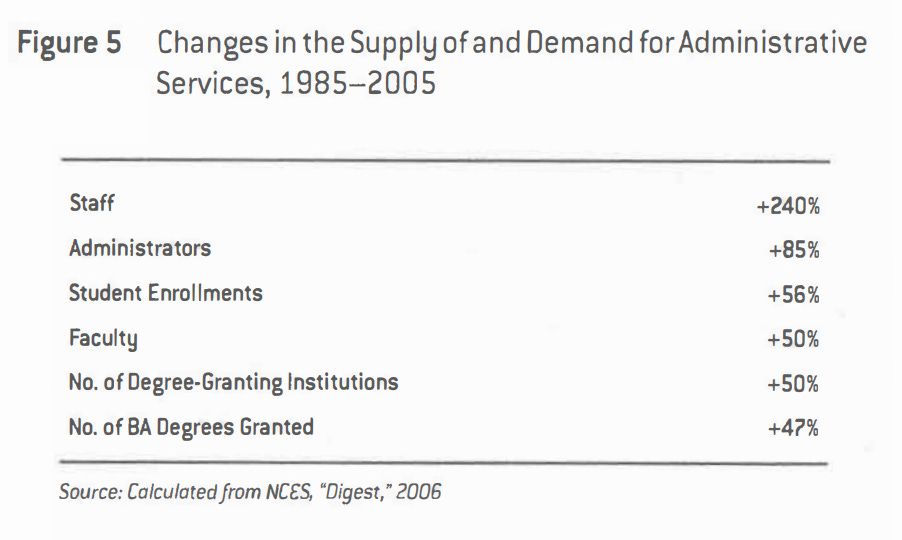

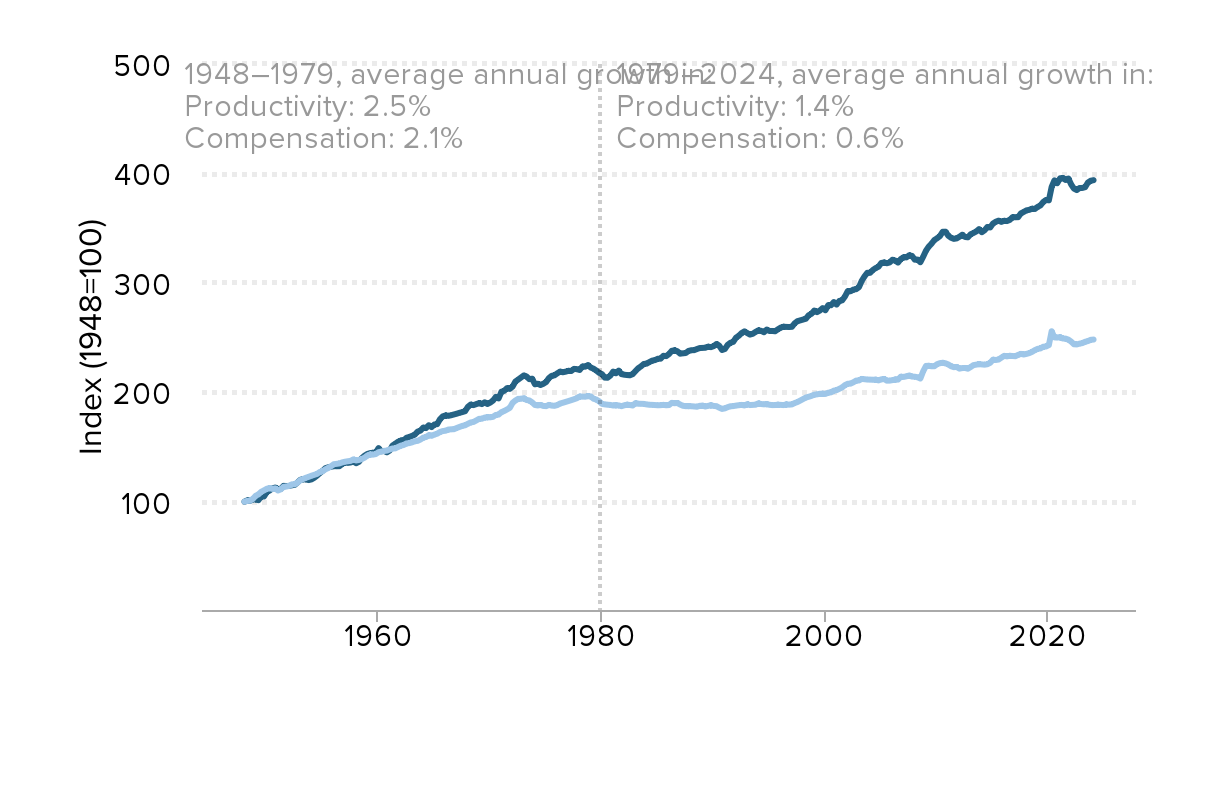

In Bullshit Jobs: A Theory, Graeber speaks to a latent widespread sentiment that people are occupying increasingly meaningless and unfulfilling jobs. Since unions fought for and won the 40 hour work week over 80 years ago, that standard hasn’t shifted since, in spite of forecasts from 20th century economists like John Maynard Keynes who predicted that technological advancements would enable us to work as little as 15 hours a week by 2030. Graeber builds a solid analysis to answer why this is, which posits that it’s not that technological advancements haven’t enabled us to work less, but that the fastest growing sector in the economy are jobs performing bureaucratic or administrative functions for largely arbitrary reasons.

In Graeber’s ideal world, he articulates that, as increasing swaths of commodity-oriented labor became automated, society would’ve gravitated towards service sector and “caring” labor, or processes which require a human component that would be difficult to genuinely replace through automation. He speculates that this hasn’t transpired primarily because of a confluence of cultural phenomena. A coffee barista or a hospice worker who loves their job may produce more tangible value than some project manager fulfilling some arbitrary paperwork or process in a megacorp, but the market generally rewards the project manager more, often by a factor of 3 or 4 times. An obsession with quantifiable value as a means of assessing monetary value and deeply engrained Protestant western ideals about the value of suffering in work drives this dissonance. Graeber elaborates:

So the more automation proceeds, the more it should be obvious that actual value emerges from the caring element of work. Yet this leads another problem. The caring value of work would appear to be precisely that element in labor that cannot be quantified.

Much of the bullshitization of real jobs, I would say, and much of the reason for the expansion of the bullshit sector more generally, is a direct result of the desire to quantify the unquantifiable. To put it bluntly, automation makes certain tasks more efficient, but at the same time, it makes other tasks less efficient. This is because it requires enormous amounts of human labor to render the processes, tasks, and outcomes that surround anything of caring value into a form that computers can even recognize. It is now possible to build a robot that can, all by itself, sort a pile of fresh fruits or vegetables into ripe, raw, and rotten. This is a good thing because sorting fruit, especially for more than an hour or two, is boring. It is not possible to build a robot that can, all by itself, scan over a dozen history course reading lists and decide which is the best course. This isn't such a bad thing, either, because such work is interesting (or at least, it's not hard to locate people who would find it so). One reason to have robots sorting fruit is so that real human beings can have more time to think about what history course they'd prefer to take, or some equally unquantifiable thing like who's their favorite funk guitarist or what color they'd like to dye their hair. However-and here's the catch-if we did for some reason wish to pretend that a computer could decide which is the best history course, say, because we decided we need to have uniform, quantifiable, "quality" standards to apply across the university for funding purposes, there's no way that, computer could do the task by itself. The fruit you can just roll into a bin. In the case of the history course, it requires enormous human effort to render the material into units that a computer would even begin to know what to do with.

I find this passage particularly interesting. The hypothetical that Graeber entertains here about a computer pining over history course reading lists and crowning the best one is now possible thanks to large language models, and unlike what he imagines, via an input format easily understood by humans and computers alike: a simple natural language prompt and some multimodal attachments to a service like ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini is enough to produce an output that is seemingly unquantifiable and rooted in human-like subjectivity.

Or is it quite that simple? I mean, it took literal droves of workers labeling data and a gargantuan corpus of existing human creative work to produce a middling approximation of human reasoning and interpretation that often hallucinates or lies, and as the video I linked above explains, it has become exponentially more difficult to raise the current standard using existing techniques. Again, I have no doubts that future breakthroughs will rapidly and suddenly raise the bar, as the transformer model that underlies these tools had done before. But ChatGPT and its competitors have been around for years now, and there is very little evidence to suggest that they have induced some mass unemployment disaster. As with prior advancements in automation, these tools so far have likely augmented existing job functions.

But let’s entertain for a moment that these tools will reach some watershed moment and have the same effect on the professional managerial class that globalization had on factory laborers and steel mills (that is to say, rendering huge swaths of jobs defunct en masse). I would anticipate that the most productive members of this cohort, with niche, highly specialized understandings of their respective fields, would suffer the most: the engineers, the scientists, the designers. As with the steel workers and factory laborers of yore, years of formal training would be rendered irrelevant if administrators with loose conceptions of the ins and outs of their field could simply orchestrate AI agents to do their bidding. Meanwhile, these same administrators, executives, and managers would exacerbate the bullshit job phenomenon for all of the same reasons they already do: arbitrary performance indicators to signify the creation of value, a desire for managerial hierarchy and underlings, and the social pressures which demand certain amounts of work, however arbitrary. People would be shuffled around the economy with massive negative ramifications for many, but the end result would likely not look that different from our world today.

That is, unless working class interests are given a seat at the table. Workers must not only be made whole for all of the existing productivity gains whose benefits they have thus far not enjoyed, but the only societal reconfiguration that would be meaningful is one which centers the interests of workers and average people. As Graeber has rightfully already pointed out, automation and productivity gains have likely already created the conditions required to provide a decent standard of living to pretty much everyone, and yet we still see so much rampant wealth inequality, poverty, and exploitation. Computers accelerating human creativity and reasoning won’t break this contradiction unless and until we refactor society to cater to the commons rather than a shrinking class of exploitative corporate masters.